Words by Faith Eckersall.

There are very good reasons why the Spitfire is the most famous British plane ever made. But, during World War II, they also became the best-kept secret in Salisbury.

After their manufacturer, Supermarine, saw its Southampton factory destroyed in the Blitz – 110 people were killed in two daytime Luftwaffe raids in September 1940 – there was a desperate race to find suitable alternatives.

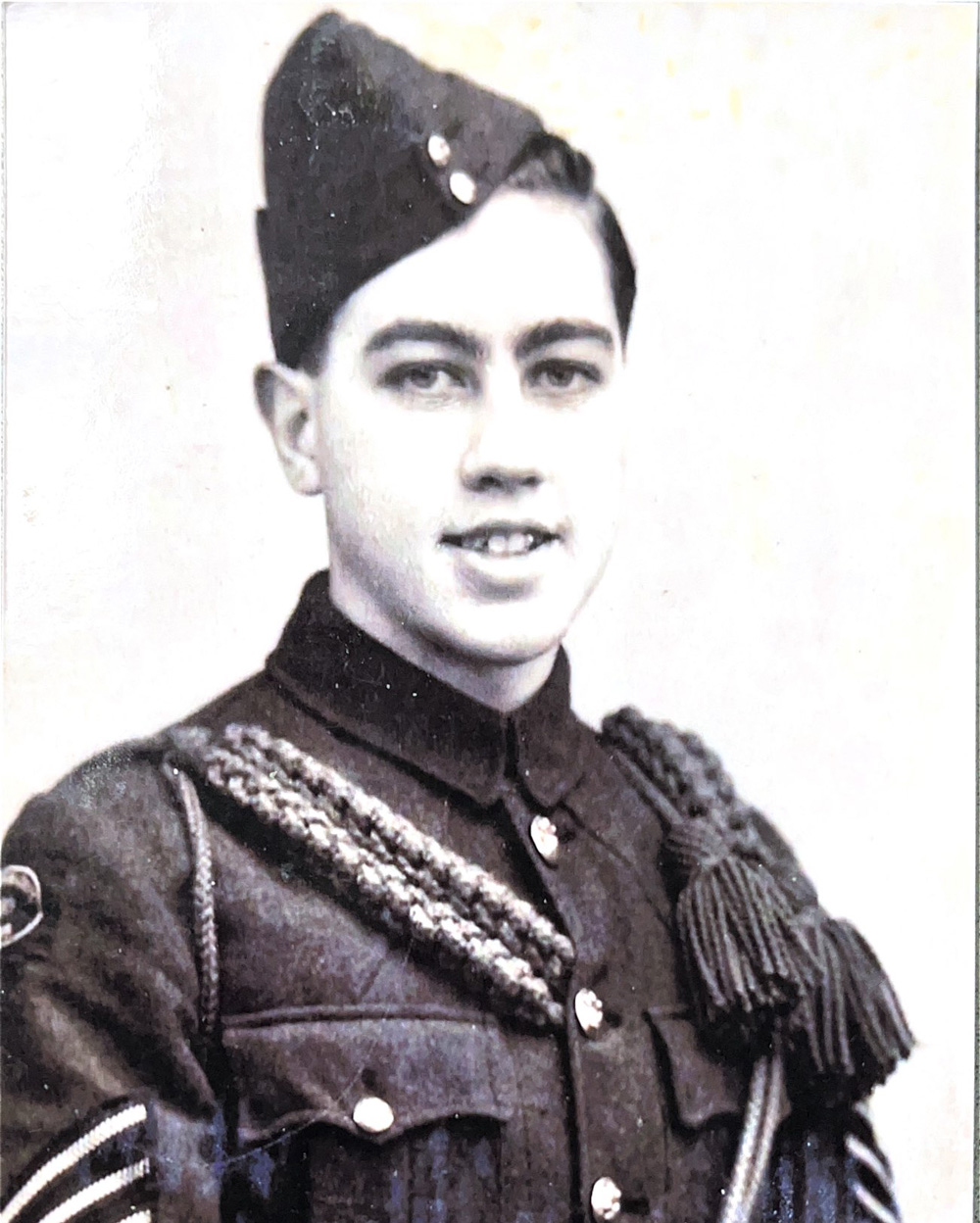

Sensibly, it was decided to spread production over a much wider area. Which is how 16-year-old Salisbury lad, Stan Gordon, found himself dispatched to London in 1941 to learn the art of aluminium welding.

“I’d left school at 14 and worked at various jobs, including the Salisbury Electric Light Company, but when you were 16 you were eligible to be called up for war work,” he says.

Stan, 95, who lives near London Road, was employed at Watt and Vincent, now A J Waters Garage, in Devizes Road. “I was sent to the British Oxygen Corporation in London to learn how to weld aluminium,” he says. “It was a good start for me, because not many people could do this type of welding at the time.”

In an era where people sincerely believed that: ‘Loose lips sink ships’, secrecy was all.

“In a vague sort of way, we all knew what we were working on,” he says. It was a feeling that many hundreds of people in must have had, as production took place over a number of locations, while the Merlin engines were produced in the North of England by Rolls-Royce.

“They built the fuselages in New Street, wings at the Wilts & Dorset Bus garage in Castle Street, and at night they’d take all the components up to High Post, where they’d put them together,” says Stan.

He worked with many older women who had trained as riveters which, he says, was: “A bit of an education!” However: “To this day, I still don’t know where the parts that I welded went to. When I joined the Spitfire Society and went inside one, I couldn’t identify which part of the plane might have been mine!”

So successful were the secret factories that Salisbury had the distinction of having provided more than 10% of all Spitfires ever produced, sending more than 2,000 to the Royal Air Force.

Thanks to the Secret Spitfire Society, a memorial replica of the aircraft was unveiled at Salisbury Rugby Football Club last year, close to one of the former manufacturing sites.

Stan’s war service didn’t end there, however. He was a messenger boy during bombing raids, going out on his trusty bike with only a tin hat for protection, to convey important messages when the alarm sounded.

“I had to report up the road to the post,” he says. “We were lucky in that we only had three bombing raids in Salisbury – I remember cycling down the Wilton Road during one in 1941 and spotting what I thought was a German plane. Sure enough, a bomb came down on the gasworks.”

By the amazing courage of the foreman at the time, who, Stan says, climbed up and plugged the ensuing gas leak, a giant tragedy was averted.

He also remembers the cherished occasion of his father receiving the British Empire Medal from King George VI, Her Late Majesty Queen Elizabeth’s father.

“Father was in the Navy in both wars – on a Dreadnought during World War I and then at Haslar Hospital in Hampshire during the Second World War,” he says. “He was recognised for his service at the hospital during the Blitz and my mother and I went to Buckingham Palace with him to receive the honour.”

Stan wore his cadet uniform, his mother her Sunday best, and both watched proudly as the King, who had served in the Royal Navy himself, spent so long chatting to his father that the ceremony ran late.

“My mother was jumping up and down, it was certainly something to tell the neighbours as very few people ever got to go inside Buckingham Palace in those days,” he says.

He ended his war service in the Royal Greenjackets, then got a job with Wessex Motors as a panel-beater and welder. He married his girlfriend, who sadly died in 1950, then re-married, becoming a beloved stepfather to his wife’s two sons.

He still takes a keen interest in Spitfires and their story, having visited Duxford and Biggin Hill airfields to see, up close, the iconic plane he helped to build. “Nothing sounds like a Spitfire and nothing looks like one,” he says. “They are the most beautiful planes ever made.”

secretspitfiresmemorial.org.uk/

Leave a Reply