Gems from The Salisbury Museum blog compiled by museum volunteer Jane Hanbidge.

Religious intolerance

In the St Edmund’s Churchwardens’ Accounts for 1610 we can read that the bells were rung, “…on the day on which we were delivered from the gunpowder treason of the papists, 10s 6d.”

It was the most money spent on bell ringing that year by a long way. Not surprising, perhaps, when we consider that the plot, led by Guido Fawkes, had been only five years before, and was fresh and still worrisome, in peoples’ minds.

Ruth Newman writes, in the 2021 edition of Sarum Chronicle, that the Roman Catholic, John Peniston (1778-1848), a Salisbury resident, officer of the Wiltshire Yeomanry Cavalry, architect and county surveyor, wrote of his feelings of “becoming really a free man” following the Catholic Emancipation Act in 1829.

However there was still some hostility in a city where only 3.2% of the population were recorded as Roman Catholic in the 1851 census of religion.

The background to all this, long and complicated, is there in the history books, and festers on in some areas, but it is good to reflect on how sentiments do change over time and generally for the better.

Plague

The middle decades of the 17th century were tough times. In 1646, in the middle of the civil war, the plague had struck in Salisbury with a vengeance.

From the churchwardens’ accounts at St Thomas, it would appear that there was some desperation when it came to finding room for burials.

The accounts show that in December 1645 they were required by the mayor to put together a census of the parishioners “by the next Friday”!

There is no explanation as to exactly what this was for but it may have been to keep track of matters during the plagues, or to do with requirements for church attendance.

But the following month, “the scantnes (sic) of the burial place in the parish and the multitude of the Inhabitants therein” had them petitioning the Cathedral for space in “the ancient burying place (belonging to the said parish) in the Litten* of the Cathedral Church…”

*burial ground, i.e. the Close.

They were prepared to open up and re-use the graves of the dead “lately buryed” but were worried about infection. All this tells a grim tale.

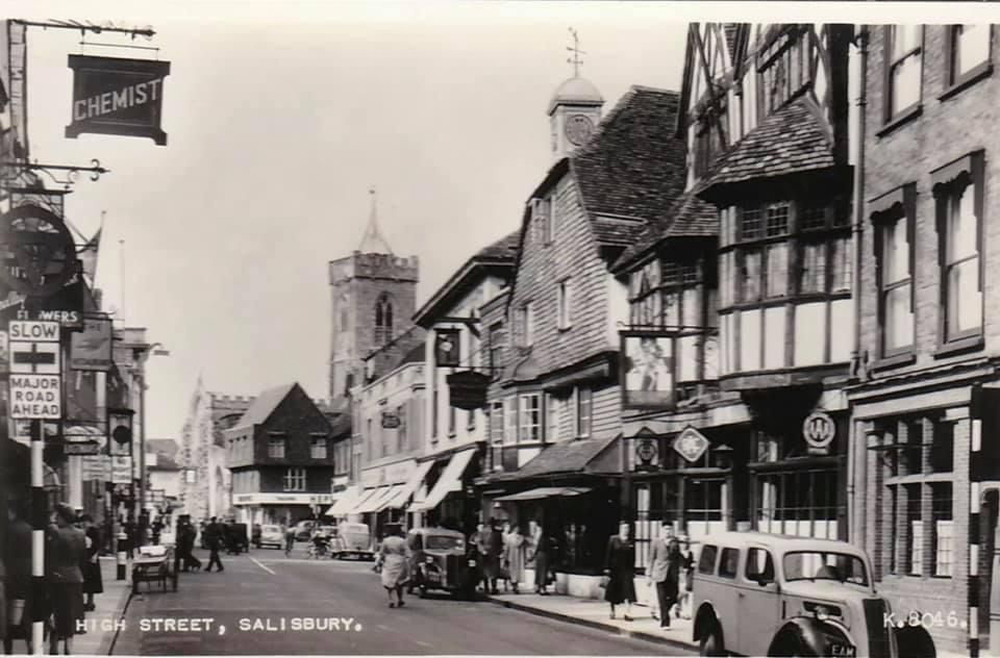

The same scene from the 1950s

Henry Fawcett

How many of us realise that the statue of Henry Fawcett (1833-1884) in Salisbury’s market place is of a blind man? He was accidentally blinded at the age of 25 by shotgun pellets. Fawcett was close to his sister, Maria, a notable woman in her own right, who helped him follow his chosen career in politics.

He later became Postmaster General in William Gladstone’s government and married Millicent (Garrett), the famous local suffragist.

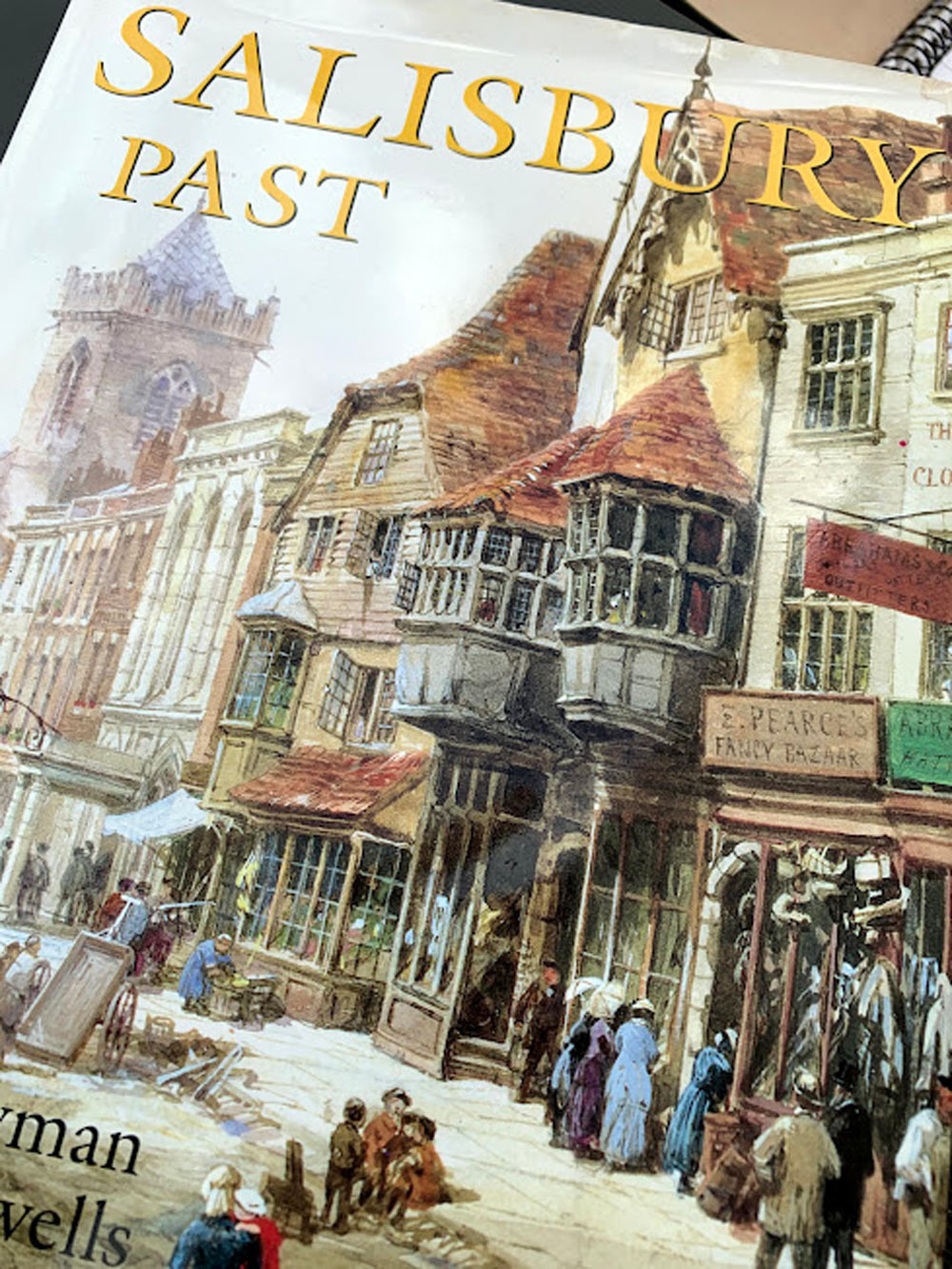

Rayner’s work on the cover of Salisbury Past

Salisbury High Street

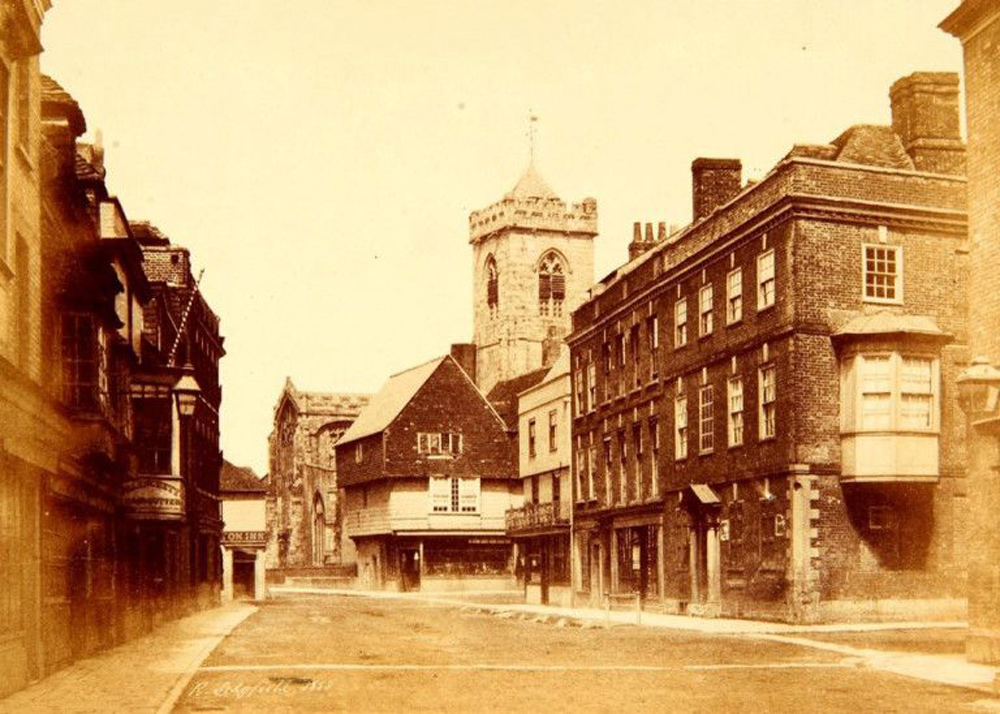

Volunteer Alan Clarke spotted one of the museum’s favourite Louise Rayner paintings from the 1870s and compared it with an early photograph

of 1853.

The photos show Louise Rayner’s work as it appears on the front cover of the Newman and Howells book*, showing the High Street in the 1870s (original painting, The Salisbury Museum), the view in the 1853 photograph and a view from the 1950s.

*Newman and Howells (2001) ‘Salisbury Past’.

Sarum Chronicle is published annually: www.sarumchronicle.wordpress.com

Leave a Reply