By Terry Grace.

By 1845, the hilltop village of Winterslow was dying and destitute, a victim of the Inclosures Act. In simple terms, this meant that the labourers who might once have worked a smallholding and had use of common ground for cattle grazing and other agricultural pursuits, found themselves working for the owners of larger farms for a pittance.

It seems that Winterslow and some neighbouring villages were hardest hit by this act and by the disregard of the wealthy landowners.

In January of 1846, The Morning Advertiser (London) sent its own correspondent to see some of the poverty in the rural areas of the south. He wrote an article entitled “Winterslow, in Wiltshire–deplorable destitution”.

In approaching Winterslow, which he described as standing in the clefts of the high range of chalky fortresses, he continues his damning prose with a telling portrait of how the locals existed. At that time, Winterslow was chiefly owned by St John’s College, Oxford and also the Fox family.

The article continues with a sketch of the truffle hunters of the village. He suggests these men are looked upon as poachers by the landlords, as their work often entails hunting by night. The wages at that time were 7s for a married man and 4s and 6p for unmarried men.

Although one of the landlords had been Dr Fox who was well regarded by the locals, his descendants took less interest in the village, “except for the interest of rent”. They kept the land for hunting and its layout was therefore not optimal for agriculture. They let the houses decay.

The author does however highlight one landlord, Squire Egerton who was resident in the village. He kept his cottages in good repair and provided employment in the village, albeit on low wages. He also provided them with fuel which was said to be a great benefit.

Travelling on to Middle and West Winterslow, which he suggests “are to a stranger all one place”, he states that the want of fuel is rigorously felt and that the houses are so deplorably broken down and defenceless against wind and rain and cold, that the want of a warm fire is worse than it might be elsewhere.

Out of the wages, which in a few cases were 8s a week but mostly 7s a week, £3- £4-10s was payable in rent to St. John’s College, Oxford for what the correspondent describes as, “miserable hovels, which it is not a figure of speech to say, are tumbling down; which are half roofless, with their gables half down, which are some without glass to the windows to the window holes; and some without doors, the wood having decayed on each side and the brickwork having fallen in”.

As if not descriptive enough, the article continues: “On the occasion of my first visit there I stood on the road or street of the village, and looked into the house of a man named Yates, at the distance of forty feet from the house, and saw the whole interior through the end which had fallen in; and inside was a motherless family of six children rolling about on the floor, amid filth and rags; and though the house was the property of the Doctors of Oxford University, who exacted and took, and added to their college income, for the

avowed purpose of education £4 a year from such a family, yet these children in filth and rags, had no education, and nobody to offer it to them. There they were as ignorant as the veriest savages, and living in a hole which savages would not live in, having another to choose, or ground to choose to build another on”.

The author then goes on to say that on a second visit to the village sometime later, nothing had changed, “save in so far as some hurdles, straw, and other makeshifts were applied to keep out the blasts of the winter of the year of Christianity 1845”. The father was now in prison for trying to feed his family by way of game.

He tells of a 15-year-old boy in this house who kept his siblings alive by poaching game. “He would have been a hero in a savage land; but in this Christian land, this hero, I will dare to call him that, is only a-something not much better than a thief. His father lived as best he could, and part of his living went to fatten the monks of Oxford; the son lives as his father lived, and scorns the bread of charity; takes upon himself the maintenance of a family of five children, himself a boy drawn to by the best affections of human nature”.

In some cases, as much as 14 weeks’ wages were consumed in rent for these hovels.

An 1845 article entitled “Conditions of the Wiltshire Peasantry” in The League, the vehicle of the Anti-Corn Law League, gives us the most descriptive and moving account of what the existence of the population was like at that time.

There were up to 40 labourers out of work in Winterslow then. The employment of a large proportion of these men was poaching and truffle hunting. As for the poaching, the writer states that it was carried on with great vigour and effect.

The price of bread in Winterslow was 13d a gallon, which was 2d more per gallon than in Salisbury. The man selling the bread told the reporter that he had closed his business because he could not get paid and in total the people of Winterslow were £200-£300 in his debt. It was impossible to live on those wages.

But the most damning thing was the state of the cottages in which these people were living.

The reporter was so shocked by this that he returned three weeks after his first visit, bringing with him an artist, who sketched these hovels so that it was recorded for history.

This cottage, as many others did, belonged to St John’s College, Oxford. The chimney had long since fallen down and not been rebuilt. The thatch of the roof had been continued over the chimney and the smoke ascended through the thatch as represented in the sketch.

The reporter was told a deaf woman was in the house when the chimney fell in – she had only left the chimney-corner a moment before the accident happened. The cottage would have been full of smoke and the occasional spark from the fire would have been extremely hazardous one would think, especially as the cottage walls were not of stone as may be suggested from the sketch. The rectangles shown are not masonry, but pieces of timber.

This sketch is of a cottage belonging to Lady Holland and is built of mud, supported by uprights and cross pieces of timber, originally forming squares, but at that point somewhat irregular figures. It was said to be in a wretched condition – a mere ruin. The woman in this hovel said that in the cold weather they paid 2s a week out of their 7s wage just for firing and they had seven or eight children. They had no garden ground and their rent was £1 a year.

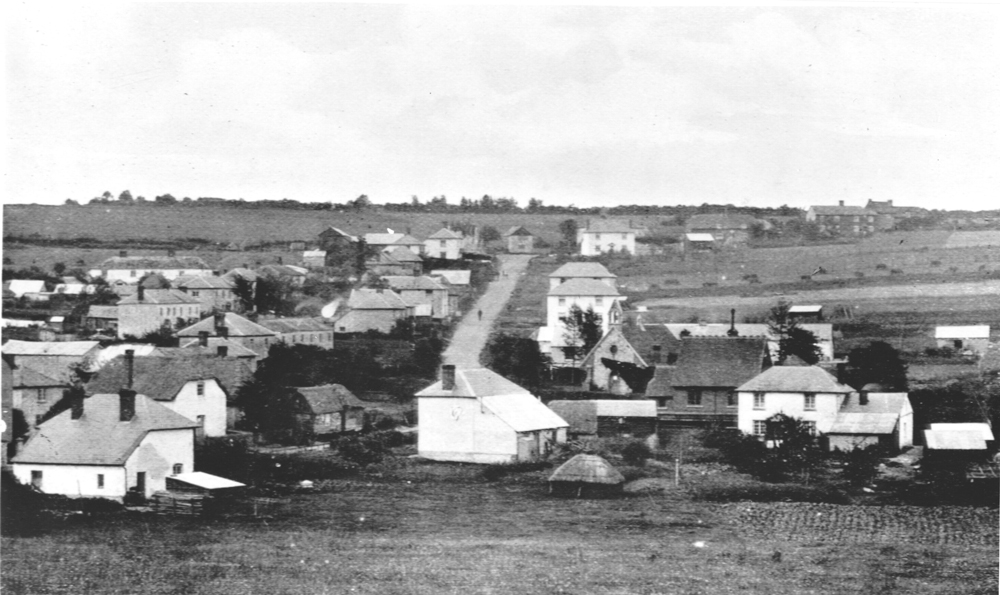

An early photograph showing the Court houses

The last two sketches, also of a cottage belonging to St John’s College, Oxford, was reported to be the worst that the visitor had seen either in the parish of Winterslow or in any other part of England, although he comments that some in Dorset were almost comparable but none in such a dilapidated state. One local man said that he could drive a horse and cart through it and he was hardly exaggerating. There were holes in the windows and holes big enough to walk through in the walls. The roof too was full of holes.

The condition of the thatched roof was in far worse condition than suggested by the sketch and was described as of wretched character. The cottage as per the previous one was made of mud supported by uprights and cross pieces of timber, forming squares. These squares had declined considerably from their original shape.

Unlike the previous cottages, this one had a considerable garden for which the occupant paid 1s a year together with the £1 rent for the cottage. He said that the rent was £3 1s 6d until the cottage got so bad.

The commentator stated that he had no way of testing this claim and did not rely on it because the character of the occupier was not a good one. “But whatever may be the rent, or character of the tenants, there can be no excuse for the landlord, who under any circumstances, allows human beings to linger out their miserable lives in hovels unfit for the abode of well-conditioned pigs.”

The visitor obviously took a dislike to the tenant of this cottage, as he continues. “There is almost a tragic interest about the history of the inmates of this miserable cottage. Not that I would hold up the head of the family as a fair sample of the depressed condition of the agricultural labour, living in fact by truffle hunting, and perhaps by poaching: and even in Winterslow he bears a character pre-eminently bad; but I cannot help thinking that under a better social system – a system in which the principle that the property has its duties, as well as rights, were not only regulated but acted upon- a system under which no class would not have the power of making all laws for all classes – such a being as the beer shop-haunting renter of this fretted tenement would be somewhat less bad, and his poor family somewhat less miserable.

The condition of this cottage is reinforced by the following graphic account of the family living there and which at times is disturbing and heart-breaking in its detail.

The reporter continues “I have met with a good many instances of families (generally, those too, in the coldest and worst dwellings) who had no blankets even in the late severe weather; and of those who had, the best off had not more than two to a bed – frequently but one – while I believe, most people found three too few in the very cold weather of last month, and that too, in houses made to keep out the cold, with doors, windows and chimneys of very different construction from that of the majority of cottages.

This family had no blankets. The children (there were seven of them), some in rags and almost naked, cowering around the embers of a fire on the hearth within the large chimney– the only sheltered spot in the house. One poor little thing, a boy about two years old, was playing among the embers, unconscious alike of the dark fate of his race and his own.

Eli Collins, a famous truffle hunter

“His little brother had been burnt to death only a short time before, while engaged as he was now. The father said his children were never without colds – not surprising certainly.”

These chilling descriptions were made on the reporter’s first visit to Winterslow but on his return three weeks later with the artist (who had sketched the houses detailed above), he was to find even more tragedy. “Rather less than three weeks ago I visited the same cottage and found the children who had recently lost their mother, under the care of their eldest sister, a girl of about seventeen. I was now informed that the girl was dead and buried. She had gone to a gentleman’s house, at a little distance, to beg, and standing about two hours in the cold and wet, she caught a cold, which from the state of the cottage, insufficient covering (there were no blankets), and the want of necessities, turned into a fever and carried her off in ten days. According to the report I heard, she died raving mad, poor thing. Her life had been short and miserable. Better to be in the grave than to go on living thus.”

One man was to save the village from ruin. In 1892, Major Robert Poore of Old Lodge, turned around the fortunes of the villagers when he purchased a farm at Winterslow and divided it into small holdings, offering these to the workers on easy payments.

After only a few years many of the villagers were making profit on these holdings and also building houses on them. This ambitious scheme, together with the introduction of a spinning and weaving industry by Poore’s wife, was to turn this village from near extinction into the thriving community it has become today.

This account is taken from Winterslow: “A most intelligent village”. Available from the History Bookshop, Fisherton St., Salisbury and online at eBay.co.uk and Amazon.co.uk.

The book covers much of the modern history of Winterslow, including Major Poore’s land Court. The Winterslow spinning and weaving industry and the famous truffle hunters is also discussed, together with chapters on the Winterslow Water Company, the Winterslow theatre history of Old Lodge, and more.

Leave a Reply